I initially wrote this essay about about “Le Circuit de Linas-Montlhéry” a decade ago. It first appeared on the old Road Racer X web site. In the intervening decade, the circuit has been saved (again) refitted with some new safety equipment. After a hiatus of several years in which the “Coupes Moto Légende,” was held in the Dijon region, it is again taking place on the outskirts of Paris. The event is highly recommended.

À la recherche de motos perdues (in two parts)

A couple of months ago, I did something every journalist should do every few years: I (re)read A.J. Liebling. He was a brilliant essayist and war correspondent, a funny guy, and an insightful observer of subjects as diverse as the sport of boxing and French cuisine. He’s best remembered for his long stint at the New Yorker, a magazine so respected by writers that it is called the[ital] New Yorker, not “New Yorker.”

Liebling wrote eloquently about returning to Paris when the city was liberated in ‘44, and described spending the last night before liberation in Linas-Montlhéry. He was bemused by the town’s gigantic racetrack, but didn’t pay it much attention. Instead, he climbed to the top of hill and looked, through a spotting scope, at Paris. That was on his mind. But reading Liebling’s reminiscence of Montlhéry took me back to my own visits there, about 60 years later...

The first time I went there, it was to write a story about an event. Afterwards, I realized the real story was about the track itself. So I went back to see the track again a few weeks later.

That first time, I got a ride with Patrick Bodden; going back alone was more involved. I had to decode French train schedules, walk for hours after miscalculating the distance from the nearest station; a whole day was shot. When I finally got there, I innocently asked permission take some pictures of the empty circuit. I was told, “Fous-moi le camp! No one’s allowed in, and even if you were allowed in, photography is strictly forbidden.” To that, the jobsworth added, “And it’s never going to be open to the public again!”

[A brief musical interlude goes here. I suggest Edith Piaf’s Je ne regrette rien—MG]

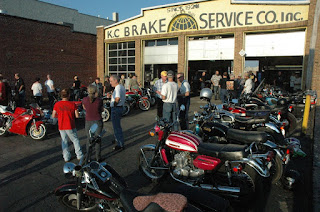

For the previous 11 years, “Coupes Moto Légende,” Europe’s biggest vintage motorcycle meet had been held at “Le Circuit de Linas-Montlhéry” on the southern outskirts of Paris. That spring, I went because I’d heard that the 2003 version of the “Coupes” was to be the final motorcycle event ever held at “Montlhéry”. The event always drew an amazing array of rare bikes. I wanted to see them, and especially hear them, in their natural habitat.

The Montlhéry circuit had remained virtually unchanged since its construction in 1924, making it a perfect setting for a vintage event. When the circuit was built it was in the countryside, but inevitably Parisian suburbs spread south and population density increased around it. More and more, locals opposed the roar of open megaphone exhausts and the traffic snarls caused by legions of fans. By the time of the 2003 event they’d gotten their wish—the locals were promised, “No more.”

But oh, what a track it was. Although the layout allowed for road courses of up to 12 kilometers in length, Montlhéry was famous for its 2-1/2 kilometer parabolic oval. Way up at the top, the banking was a real old “wall of death.” If you had the guts and suspension for it, you could ride any motorcycle ever made all the way ‘round absolutely wide open. You think I’m exaggerating?

Raymond Jamin, who engineered the track, calculated the rising slope so that up at the guardrail, a motorcycle could run through the turns at 220 k.p.h. with completely neutral steering. To build the banking up high enough, and make it strong enough to absorb the g-forces generated by the massive speed-record automobiles of the day, Jamin used 8000 cubic meters of concrete, reinforced with 1000 tons of steel.

Fame eluded Jamin, but his race track is a monument to the modernist style that appropriately became known as “brutalism.” Now, it’s listed in the official register of French historic sites and monuments.

The bowl was an ideal place to set speed and endurance records, and they were set here, by the handwritten, leather-bound book-full. Five years after the track was built, Herb Le Vack rode a Brough Superior to the world’s first closed-course lap of over 200 k.p.h. That bike, a 1927 model SS100 Pendine had been tweaked by Freddie Dixon. Before Le Vack rode, it was raced by George Brough himself. It’s currently owned by Peter Lancaster, a collector—like everyone here at the Coupes—who understands that even precious bikes need to run to live.

In 1952, Norton’s race engineer Joe Craig was staggered by the speed of the Gilera four-cylinder Grand Prix bikes. He responded by building the Norton ‘kneeler’, trying to make up with streamlining what the single-cylinder Manx engine gave up in horsepower. English GP ace Ray Amm, aided by Eric Oliver, set a total of 41 records on that Norton when they brought it here in the fall of 1953.

The noise they made!

Norton, blaat.

Brough, MV, roaring (the twin pitched flat, the four on song.)

Honda six, Guzzi eight. I winced when they were revved. Partly due to the earsplitting sound, and partly because I couldn’t ignore the potential for mechanical mayhem within those irreplaceable crankcases.

At a certain moment, it occurred to me that, yeah, I was getting an echo off the banking, but the parabolic shape was directing the bulk of the sound straight up into the heavens. High flying birds, at least, must’ve wondered “What the?..”

By Sunday, we had bounced too many shock waves into the clouds, and it started to rain. Thousands of people; most of the riders, exhibitors, and swap meet traders had been bivouacked under the infield trees. Handwritten signs dissolved into papier maché. “For Sale”, “Wanted”, “I’ll sell you this rolling chassis, or buy a motor if you have one to fit it”. (Either way at least someone could leave with a whole motorcycle.) One sign taped to a frame desperately asked, “Does anyone know what this is?”

In the rain, anything being sold under an awning suddenly got a lot more interesting. I lined up for some ‘frites’, behind a couple in their late fifties or early sixties. She was wearing a tweed suit, white blouse; a brooch, little gloves. As though she’d just come back from mass. He was holding something made of black plastic: the air filter housing for a Suzuki GT750. “You see, here’s where the filter goes,” he said, pointing inside. “And is that something,” she asked, “which will have to be cleaned?”

They had both been faking this conversation since Suzuki introduced the GT. She was pretending that she cared, and he was pretending to believe her. Both were visibly relieved when I leaned in to ask, “Did they call GT750s ‘kettles’ here in France?” That way he could start talking to me instead.

That year as always, the actual “coupes”—the cups—were awarded by a jury. There were classes for absolutely everything, from utilitarian mopeds to bona-fide works GP bikes. Such bikes are often ridden by the men who originally raced them. Kenny Roberts made the pilgrimage in 2002; Agostini came to Montlhéry almost every year. In total, about a thousand machines took their laps during each event.

Although the promoter sternly warned, “This is not a race!” putting riders like this on vintage race iron could only lead to one thing: racing! Even Sammy Miller—otherwise seemingly immune to the effects of time—lowsided, earning a ride back in the pace car, looking as close to embarrassed as a member of the Pantheon can look.

Finally, it poured. In the infield, people folded wet tents, stuffed damp sleeping bags into sacks. “That’s the part that I would hate,” my friend said, as we slogged past a vendor loading his inventory of cycle parts—now wet, and even rustier—back onto a trailer. Vehicles inched out on muddy tracks.

I hope you don’t mind if I leave you here, in the rain, for a week. It’ll do you good. Build character. Me? I’m heading over to a large tent, where I can hear an accordion and tinkling champagne glasses, but I’ll be back here next Thursday to conclude this essay.

Au revoir, Marc

☂

Last week I left you in the rain, as the horde of fans and swap meet treasure hunters abandoned the Circuit Linas-Montlhéry in the face of an advancing rainstorm.

I retreated to Eric Saul’s huge tent. Saul, who won a couple of Grands Prix back in the day, occasionally promotes classic races based mostly on the rugged Yamaha 250 and 350 twins that filled GP grids in the 1970s. The day before, Eric had highsided his Bimota 250 and broken his collarbone, for the nth time. I learned that the French word for “highside” is pronounced, “eye-side”.

“I think,” said Saul with a one-sided shrug, “that there might have been oil on the track. Have a glass of champagne.” Hundreds of people were packed in with us, the hard core that didn’t want to leave, even though the Coupes Moto-Légende was over. Eric’s girlfriend, also a racer, was playing the accordion. Some song that was so French it hurt. She was tall enough, pretty enough (and fast enough by the way) that it looked and sounded good on her. I thought about pushing through the crowd to say hello to Giacomo Agostini, but I stayed on the fringes.

It’s not an accident that the expression “joie de vivre” is French. Eventually though, all things must end. The party fell quiet and the last of us filtered out, leaving the great track silent once and for all–if by “all” you mean, the public.

What does the future hold for Montlhéry? The land belongs to the government. Decades ago, the track and associated buildings were handed over to UTAC, a company which provides testing and consulting services to the car industry. UTAC, in turn, is controlled by Renault and Peugot/Citroen. This tangled ownership always made it easy to duck responsibility. When Montlhéry locals complained about noise and traffic, the administration said, “What can we do? The land belongs to the government; they’re the ones who made it a national monument; we’re sort of obliged to open it to the citizens every now and then.”

At the same time, when 40,000 Coupes fans got up in arms over the impending closure of their favorite track the administration said, “Well, it’s not us that want to close the circuit.”

But it was them. UTAC never wanted the public on the site. They do almost all their physical testing in modern buildings built outside the track, and their business is increasingly done with computer simulations. The company’s web site doesn’t even mention the legendary oval.

The road course was occasionally rented out to car clubs, but the owners said the use they got from it, and the revenue it generated, didn’t justify the cost of basic annual upkeep.

A few years ago, they got the perfect excuse to close it: the French government being, well, French has a committee that exists for the sole purpose of homologating the country’s race tracks. Every track needs a valid certificate to stage events. For Montlhéry’s certificate to be renewed in 2004, someone would have had to spend $15 million repairing cracks in the concrete and repaving the whole thing.

“15 million!” UTAC’s spokesmen acted suitably taken aback, and sputtered, “Who’s got that kind of money? We’ll have to stop holding public events.”

Without a showcase event like Coupes Moto Légende, le Circuit de Linas-Montlhéry faces continued neglect, and slow decay. Eventually, it will be unusable, and the owners will be glad to padlock it once and for all. Weeds will push up through the cracked asphalt and vines will slowly overtake the concrete banking.

Motorcycling itself only goes back a hundred years; and Grand Prix racing barely goes back 50. So until now, as motorcyclists, the most interesting parts of our past have been held in our collective living memory. As a historian of our sport, I have always liked the idea that I could talk directly to the people who made our history—that I could see their motorcycles run, and hear them.

No one would have thought—riding like we did, half the time without helmets—that we’d even last long enough to reach this point. But as time marches on, motorcycling’s history is starting to reach back past living memory. Into history history. That would be what? Dead memory?

It’s funny. I went to the Circuit de Linas-Montlhéry for the bikes. Because it might’ve been my last chance to see and hear a bike like that Norton kneeler in its original context. I thought that hearing it would somehow make that memory my own; real, not just a historical note beside a static display.

Then I went back a second time for the empty track. I was prevented from seeing it, not because there was any secret testing going on there that I might photograph, just because a typical, emasculated French petty functionary relished the opportunity to say “no.”

I never expected to be so interested in the track. There was a certain, melancholy poetry to being denied a final visit, not that there’s any great philosophical conclusion to draw from it. Except that while it’s worth it to keep our history alive, it’s also important to remember the things we’ve lost.

This story is included in my book, On Motorcycles: The Best of Backmarker. If you enjoyed it, buy a book now and give it to a friend for Christmas. Then, you can borrow it back and read dozens more tales like this one.